Sovereignty today is about ownership and control over IT infrastructure—not just legal jurisdiction or physical assets. In just one quarter, Microsoft’s shutdown of Nayara Energy’s cloud services, Trump’s 50% tariff and mass US visa cancellations for India’s tech workers revealed how dependent we’ve become on US controlled data, platforms and talent pipelines.

Three unrelated events, one strategic lesson: when data, platforms and talent sit under foreign jurisdiction, the nation’s economic and security calculus is hostage to external politics. American Big Techs, cushioned by Indian user data and revenues, can still switch off essential services overnight. It is time to re-evaluate the conciliatory approach embedded in the Digital Personal Data Protection Act (DPDPA) and move from permissive “soft” localisation to enforceable “hard” localisation for all sensitive and strategically valuable data.

Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023 – Official Text

Why India’s Digital Sovereignty Matters More Than Ever

Alvin Toffler’s prescient observations in “The Third Wave” have materialised with chilling accuracy in today’s digital landscape. Toffler argued that in the post-industrial information age, “the central resource buoying the Third Wave is not land, labor, or capital, but knowledge”. He further emphasised that power in any epoch is determined by the triumvirate of knowledge, wealth, and violence. Today’s geopolitical tensions validate Toffler’s framework: those who control information infrastructure wield unprecedented power over nations ostensibly sovereign in traditional terms.

Alvin Toffler’s The Third Wave

Risks of Cloud Dependency

The Microsoft-Nayara Energy incident exemplifies this new power dynamic. Despite Nayara being an Indian company operating under Indian law, Microsoft’s unilateral decision to suspend services based on EU sanctions demonstrated how foreign jurisdictions can effectively override domestic sovereignty.

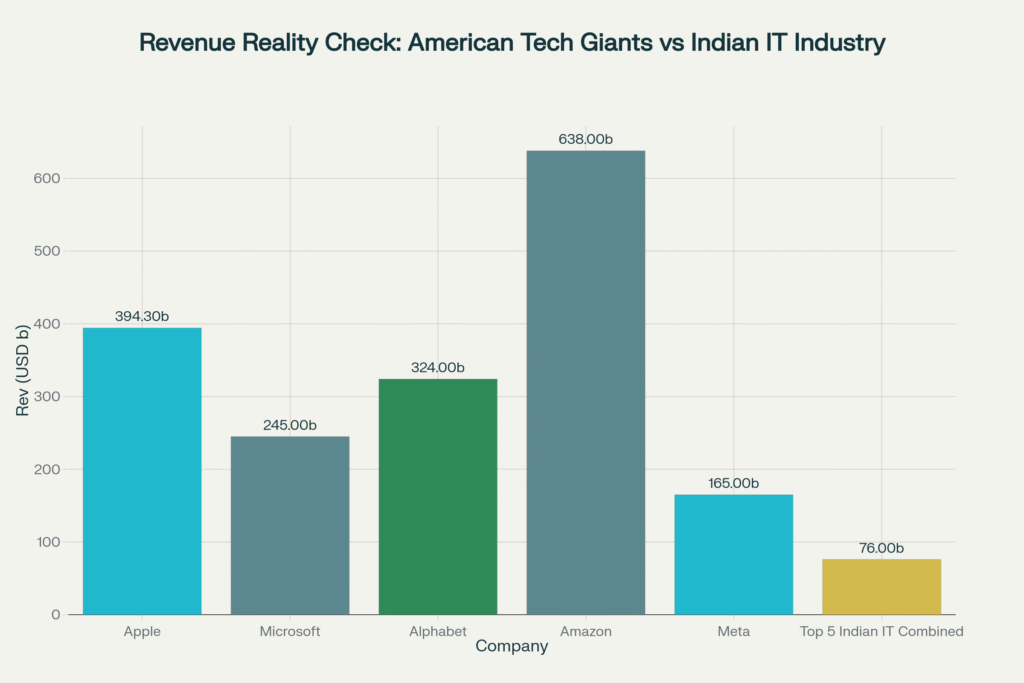

For decades, Big Tech enjoyed dominance: setting economic, cultural, and social agendas, often overruling governments. Globally, digital platforms “became the most efficient wealth-creating apparatus the world has ever seen,” operating with near-independence from national borders and policies

Ola founder Bhavish Aggarwal’s coinage of “techno-colonialism” captures the essence of contemporary digital exploitation. His analogy to the British East India Company is particularly apt: just as colonial powers extracted raw materials from India and sold back manufactured goods, American Big Tech companies extract Indian data, process it abroad, and monetise it back to Indian consumers.

The statistics are staggering: Bharat produces 20% of the world’s data, yet only one-tenth is stored domestically. The remaining 90% flows to global data centres predominantly controlled by American corporations, processed into AI algorithms, and sold back to the country in dollars. This extraction model exemplifies what Toffler identified as the shift from “brute-force economies to brain-force economies”, where data becomes the new raw material for wealth creation.

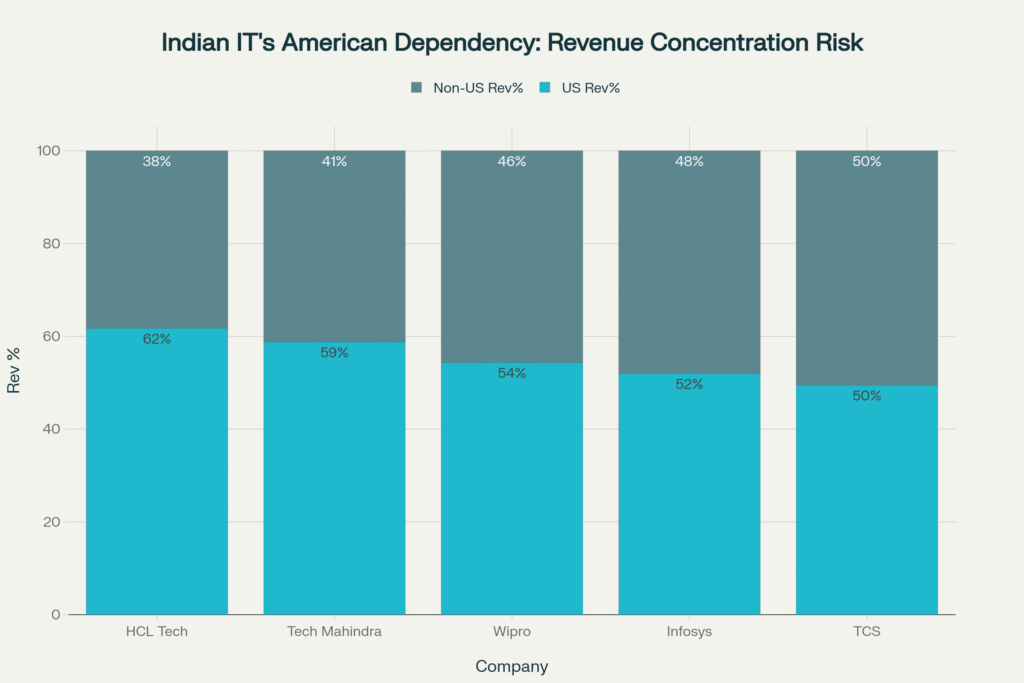

The scale of American Big Tech operations in the country further underscores this dependency. Meta reported a 24% increase in gross advertising revenue in FY24, while Microsoft witnessed a 38% rise in standalone profit. These companies collectively employ over 208,000 people in Bharat alone, creating a workforce dependency that compounds the data extraction vulnerability.

Scholars of “data colonialism” argue that Big Tech replicates classical extraction by appropriating the raw material of the 21st century; human behaviour and repackaging it for profit abroad. Five US firms now sit atop the world’s market-cap league precisely because they harvest, analyse and monetise data from markets like India while keeping high-value analytics and AI R&D at home.

A soft localisation clause that only asks for an Indian “mirror copy” does little to change that equation. Data gravity; the economic value that attracts investment in AI, cloud and silicon will still pull the most advanced capabilities back to the parent jurisdiction.

DPDPA’s Insufficient Response: The Committee Approach Fallacy

India’s Digital Personal Data Protection Act (DPDPA) 2023, while representing progress, fundamentally misunderstands the nature of the sovereignty challenge. The Act’s “blacklist” approach to cross-border data transfers and its proposed committee-based restrictions on Significant Data Fiduciaries represent classic soft localisation measures; inadequate to address the scale of American technological dominance.

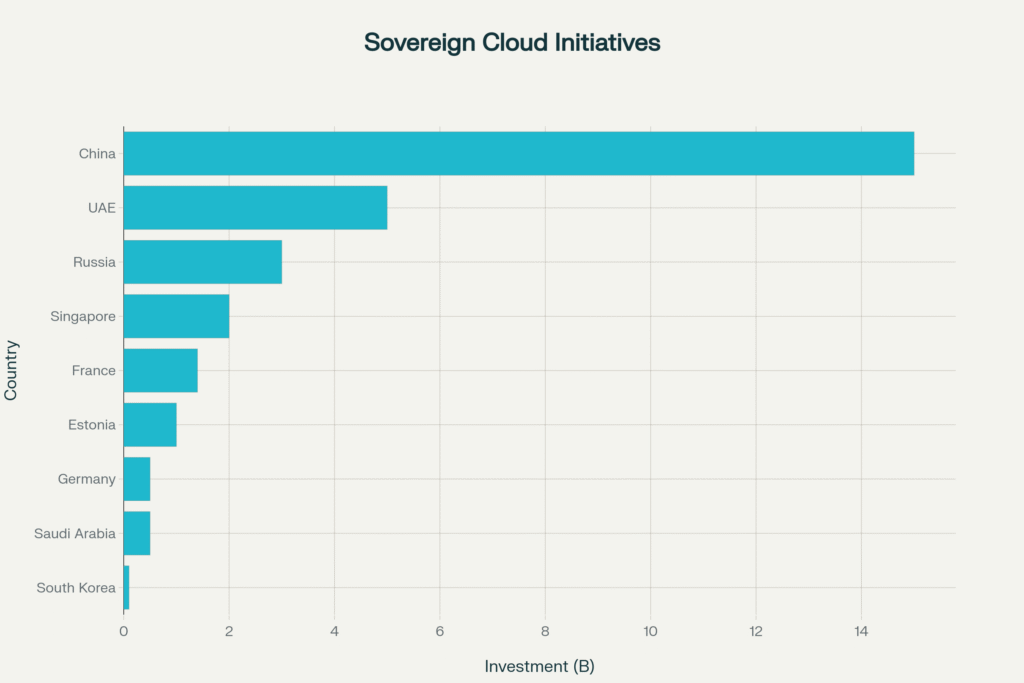

The recently released Draft Rules further dilute even these modest restrictions. By empowering government committees to impose localisation requirements on a case-by-case basis, India has essentially institutionalised regulatory uncertainty while providing American platforms with multiple avenues for circumvention. This approach contrasts sharply with China’s hard localisation requirements or Russia’s comprehensive data sovereignty framework.

The committee approach embedded in the Draft Rules reflects what policy experts characterise as “excessive executive discretion, absence of privacy and security considerations, and a trade-restrictive approach”. Rather than providing legal certainty, this framework creates conditions for continued American leverage over Indian data governance decisions.

India’s unique position as both a major data generator and a significant technological capability holder suggests that hard localisation could be implemented with fewer disruptions than in smaller economies. The country’s robust digital public infrastructure, including Aadhaar, UPI, and the India Stack, demonstrates indigenous capacity for large-scale data processing.

| Country | Approach/Initiative |

| Estonia | X-Road digital backbone, e-Residency, 100% domestic control |

| Singapore | Sovereign Commercial Cloud (GCC), partnership frameworks |

| South Korea | Digital Platform Government, indigenous cloud and security |

| France/Germany | EU sovereign cloud ventures (Bleu, T-Systems) |

| UAE/Saudi Arabia | Locally owned AI datacenters, strategic partnerships |

A calibrated hard-localisation blueprint

To secure digital autonomy and strengthen national resilience, India should adopt a tiered approach to data localisation based on strategic value.

Highly sensitive data such as defence records, critical infrastructure telemetry, genomic information, and financial-system signals belongs in the Red Tier and must be stored and processed entirely within India, ensuring full localisation. For large-scale personal data, classified as Amber Tier, processing may be allowed by foreign cloud providers only if it occurs in Indian cloud regions with zero-knowledge encryption and on-shore management of security keys, maintaining strict oversight. Less sensitive commercial or anonymous datasets, in the Green Tier, can continue to flow freely without special restrictions.

Additionally, India should require operators to establish physically and logically segregated sovereign cloud regions within the country that remain inaccessible to foreign legal demands. Market access can be leveraged by imposing reciprocity clauses, compelling Big Tech companies to set up AI training clusters within India that are proportionate to their domestic user base, thus converting local digital activity into skilled employment opportunities.

Finally, to safeguard national cyber infrastructure, India needs to upgrade its cyber command and CERT-In by establishing an autonomous Data Security Board on the lines of Israel’s National Cyber Authority, bringing together joint expertise from military and civilian sectors to proactively defend against evolving digital threats.

National Security Imperatives: Beyond Economic Considerations

The standoff between Nayara Energy’s refinery and Microsoft’s license keys vividly illustrates a new reality: in today’s world, control over code is as critical as control over steel once was. When trade tariffs, sweeping sanctions, and visa restrictions can disrupt entire industries overnight, India’s true independence now rests on the strength of its digital infrastructure.

India’s economic stability and security are vulnerable to decisions made by distant technology firms and commercial interests: not just governments, but powerful corporations that can act rapidly under pressure. Real sovereignty in the age of AI demands far more than simply hosting data at home; it requires mastery over the underlying algorithms, semiconductor chips, and quantum-proof security technologies that form the backbone of modern digital systems.

The ongoing tug-of-war between states and tech giants makes it urgent for India to implement robust laws and technical safeguards, ensuring that national interests always take precedence over corporate agendas; especially in critical sectors like energy, finance, and public infrastructure. Soft localisation offered some protection, but now the government must take bold steps: not out of mere protectionism, but as a rational shield against mounting geopolitical risks.

Inaction can rapidly turn the comfort of foreign technology into a threat to national stability. Only by securing access, asserting ownership, and building domestic capabilities can India truly safeguard both its economic future and strategic autonomy in an era dominated by digital power.

Data Embassy: How India Can Dominate the Next Digital Revolution